About: A photographic journey: 1985 - 2000

“What Roman Vishniac did in illuminating the vanished of Eastern European Jewry before the Holocaust, Serotta’s book will in its own turn do for the living, contemporary history of Europe’s Jews.”

When I made my first trip to Bucharest in December, 1985, I had no intention of beginning a fifteen year journey through the Jewish communities of Central and East Europe. In fact, I hadn’t been in a synagogue or thought anything about Jews since I had paid my dues by having a bar mitzvah in Savannah, Georgia, in 1962.

I was in Bucharest photographing and writing a story for the soon-to-fold Travel-Holiday Magazine, but one snowy morning as I was walking on Strada Sfanta Vineri I looked up to see an ornate Moorish synagogue that looked very much like the one I had been bar mitzvahed in. On a whim, I went inside. An elderly man was sweeping the sanctuary and when I started speaking in English, he motioned me over to the office building next door.

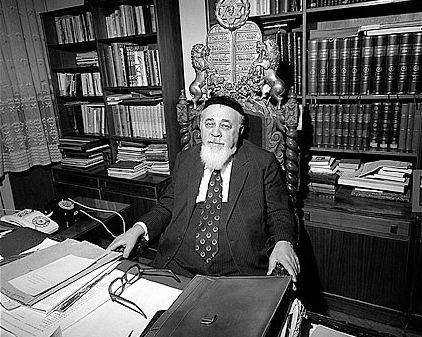

A few minutes later I was sitting in the office of Chief Rabbi David Moses Rosen, who was nearly as round as he was tall and was sitting in what appeared to be a throne. He poured two thimbles of slivovitz for us and it was the first time I had ever tried the fiery plum brandy. When I told him I was in town as a freelance photographer and journalist but had not come to write or photograph anything on Jews he immediately told me that is exactly what I needed to do because in Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship, where people were consigned to a single forty watt lightbulb per room, where there was barely any heat coming out of radiators and even less meat in the shops, the old rabbi said he had established a social welfare network as good as any in the world and it would make a great story for a reporter.

“For Travel Holiday?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Jewish papers. They’ll buy it,” and he then sent me over to the Jewish community soup kitchen around the corner for lunch.

Sitting there, I tucked into a slab of brisket the size of the Manhattan telephone book and started chatting with college students as well as elderly Jews. It was noisy, lively and fun. I said to myself, ‘Wow, this is just like the Jewish community in Savannah, Georgia, where I grew up.’ Then I realized: ‘No, Savannah is like this, not the other way around.’ I thought again, ‘This is just like the old country!’ And I corrected myself again (with the aid of another thimble of slivovitz), ‘No, it’s not like the old country. It is the old country. And I’m in it!’

In a sense, I never left. I was thirty-five years old then; I’m nearly seventy as I write these lines. And over the next fifteen years I documented Jewish life throughout Central and Eastern Europe with my camera, with my pen, and starting in 1996, with a video camera as I made a series of films for ABC News Nightline.

But back in 1985, I had no idea what I’d be doing and I returned to my home in Atlanta, Georgia to churn out freelance articles. Over the next three years, as I made trips of longer and longer duration to the region, I decided to sell everything I had and move so that I could really document Jewish life in a part of the world most people said had vanished. Thinking about where I could live proved easy. With Communism still in place, the only city I could set up residence in was Budapest. Besides, it had the largest Jewish community by far and I made the move in March, 1988.

Out of the Shadows

I had already started working on the book that in 1991 would become Out of the Shadows. In fact, I guess I started the minute I took that picture of Rabbi Rosen. Since Communism was kind enough to collapse in the fall of 1989, the Jewish communities I had begun documenting changed almost completely—except for Romania. Rabbi Rosen would stay in charge until his death in 1994. In Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, however, heads of Jewish communities, all of whom had slavishly toed the Communist Party line, were thrown out in early 1990. Soon after, as Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union broke apart into successor states, new Jewish communities sprang up there, too.

Before Out of the Shadows was published and throughout the 1980s, there was a growing cottage industry of books published on The Last Jews of… (fill in the blank: Eastern Europe, Poland, Romania) along with a plethora of black and white studies of concentration camps.

It was understandable. The enormous Jewish world that had flourished between the Baltic and the Aegean Seas had been all but wiped out. The Nazis did the murdering, the Communists chased out those who were observant afterwards. So I understood why photographers were focusing on these ‘last of’ studies. But I had no interest in that and I thought: we already know how few Jews there are left and we’ve known it for decades. What are their lives like now?

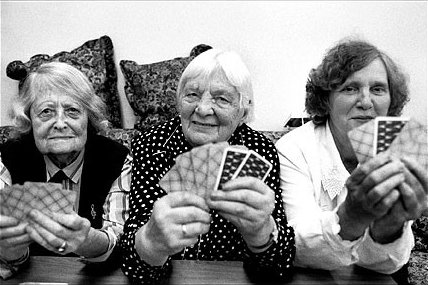

From 1985 to 1991, I stayed in people’s homes, slept on their sofas, ate at their tables and listened to their stories. I visited as many people as I could, went to Jewish community functions, memorial services, funerals, weddings, graduation ceremonies and summer camps. Whatever Jewish life there was, I wanted to capture it and from left to right above, those pictures were taken in Katowice, in Poland, the Pirovac summer camp in what was then Yugoslavia, and in Iasi, Romania.

I also photographed synagogues, but not especially well since architectural photography is an art until itself and I also photographed cemeteries, like the melancholy, tree shaded cemetery in Brno, Czechoslovakia.

Out of the Shadows was published in 1991 to extremely good reviews. Judith Mara Gutman summarized it best in The New York Times on October 6, 1991, “Get ready to shake loose a whole host of accepted notions about Jews in Eastern Europe…The photographs are surprising, poignant and convincing, depicting secular activists and religious adherents, rock concerts and reopened synagogues, professors, travel agents, rabbis and, always, children.”

The International Center of Photography in New York—one of the most prestigious places to be shown—had been founded by Cornell Capa, brother of the famed war photographer Cornell Capa. Cornell took a liking to my work, offered me a show, and he wrote of Out of the Shadows:

“What Roman Vishniac did for the in illuminating the vanished of Eastern European Jewry before the Holocaust, Serotta’s book will in its own turn do for the living, contemporary history of Europe’s Jews.”

Kodak Germany sponsored a European version of the exhibition, which would travel to some twenty-four galleries, public spaces and museums over the next six years and a German version of the book was published in 1992. Everything I had wanted to accomplish I did, and it was time to move to a new project.

Survival in Sarajevo: Jews, Bosnia and the Lessons of the Past

In 1991 I moved to Berlin, where I began working on what was meant to be a second book, on Germans and Jews. But after I had invested two years in the project, something happened in 1993 that changed everything. I was having coffee with a friend, Tom Gjelten of National Public Radio. Tom had told me something he had just seen while covering the siege of Sarajevo: that the tiny Jewish community had turned itself into a humanitarian aid agency and it was staffed by Jews and Muslims, Serbian Orthodox and Catholic Croats. Hadn’t I been to Sarajevo before the siege and didn’t I know people in the Jewish community? I did indeed, but never, I told him, would I go into a war zone.

Two weeks later, I was riding in the back of an armored personnel carrier through the streets of Sarajevo and stepped out and walked with wobbly knees into the community center, which I had visited in 1988 and 1989. I met my old friends who were running its humanitarian aid agency, started making notes and pulled out a camera. They slid the slivovitz across the table.

I made four trips to Sarajevo between November 1993 and February 1994 and spent a total of forty-four days under fire (which was nothing compared to other journalists and that was nothing compared to the poor souls trapped there) and then I followed the story to Israel, where I photographed and wrote about Sarajevans trying to set up new lives for themselves.

I would return to Sarajevo twice more during the siege but by this point, I had enough pictures and stories to produce a book, which I did in late 1994. Survival in Sarajevo: Jews, Bosnia, and the Lessons of the Past was published by Brandstaetter and DAP (Distributed Art Publishers) and sold over 15,000 copies in English and 5,000 in German. The photographs from this project are the strongest and most compelling I ever made as I wanted to capture what it was like to live in a war zone. Photographs from this collection were purchased by the Touro Museum in New Orleans, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the (late) Corcoran Museum in Washington.

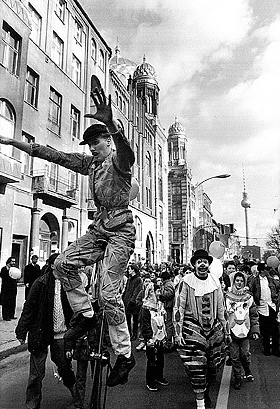

Jews, Germany, Memory

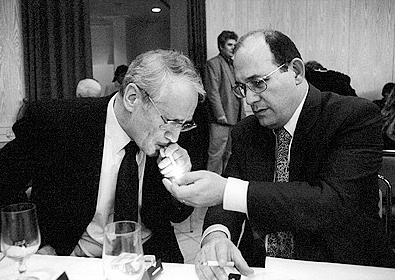

My goal was to capture what Jewish community life was like in Germany in the 1990s; how the tens of thousands of Soviet Jews were being integrated; how Germans related to the troubled, uneasy relationship they had with their past; and finally, I wanted to spend a week with a group of German Jews returning to their country for the first time since the 1930s.

Photographing in down-at-its-heels Central Europe was one thing; photographing a war zone something else; but trying to capture a relationship in a western European country was something else again and the photographs would be more subtle, and, since it had to do with Germans and Jews, a lot more ironic.

1996-2000

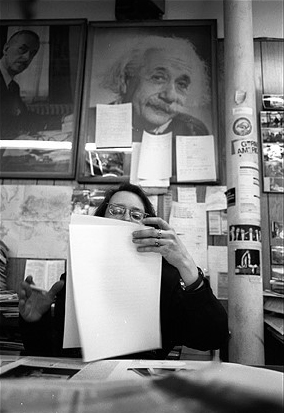

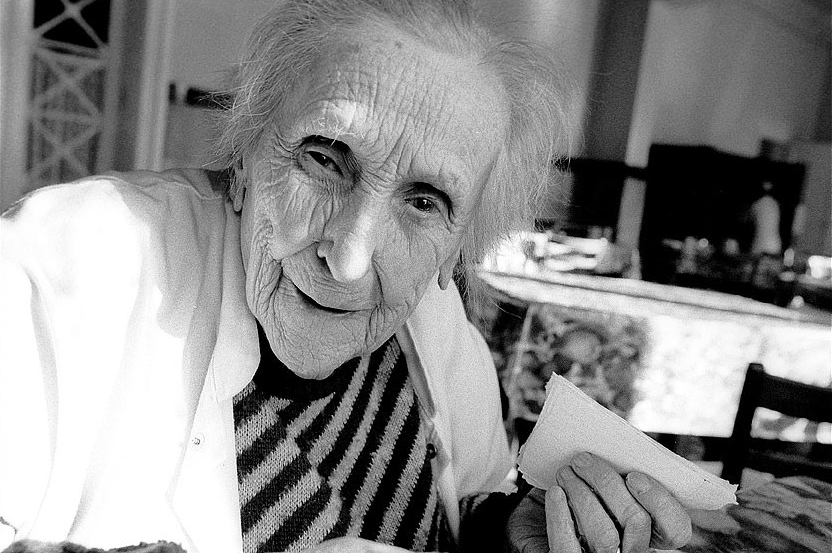

In 1996 I made my first twenty-minute documentary for ABC News Nightline, and that was followed by three more. The first film told the story of looking for the Sarajevo Haggadah, and The Washington Post called it “perfect television.” I made a second film on a boy imprisoned in Theresienstadt, then one on the original Budweiser beer, and a fourth, called Aunt Rosie’s Kitchen, about a Jewish old age home in Arad, Romania. Aunt Rosie, pictured above, was ninety-three-years-old when I took this picture and still had three more years to run her kitchen.

As I explain in the accompanying chapter on Hungary, that is where I went home with elderly Jews every afternoon, who sat with me on their sofas, opened their family albums, and told me stories about the people in those pictures. And that is what I decided to do next—to create a way of preserving Jewish memories and the photos that went with them.

During this four-year period, I also photographed for Time Magazine and other publications and broadened my work to Ukraine, Russia, Greece and the Baltic states. At the same time, I also went back to almost all of the Jewish communities I’d been working in, but by 2000, I realized that I had accomplished everything I had set out to do: to capture Jewish life in a part of the world many had given up for dead.

Jewish life will never be what it was before the Holocaust and the world will forever mourn. After all, the Jewish communities that gave the world Freud and Kafka, Mahler and Freud, are all but gone and they are likely not to produce such light again.

But there are Jews in each of these countries today, and during that fifteen year window when I watched them come out of the shadows and into the light, I wanted to document each step that they made, and I have now preserved those images for decades to come.